On Seriousness

The precious resource America lacks

A few years ago, 4chan users began a brilliant psyop targeting the Islamic State. ISIS fighters— often depicted as powerful monsters with AK-47s in hand—looked different after the Internet came for them. 4chan waged its misinformation war against terror by superimposing yellow rubber duck heads on the faces of ISIS fighters, replacing their Kalashnikovs with toilet bowl brushes.

Terrorists are serious people. Anyone willing to strap a bomb on their chest and walk into a crowded restaurant believes something so profoundly that you and I can’t fathom. Many young men (it’s mostly young men) are attracted to the seriousness of the mission. Terror networks recruit by using propaganda to create fear, showcase power and convey the extreme seriousness of the organization. And ISIS was a brilliant disseminator of propaganda, going so far as to create a Conde Nast-styled magazine called “Dabiq,” which served as the Architectural Digest for the caliphate.

But a rubber duck riding on a tank through the streets of Mosul is not serious. It’s actually very funny. It’s also emasculating, something that 4chan users know how to do with great effect. You don’t win the war against ISIS by allowing aspiring warlords to seem like serious men. While ISIS was defeated through conventional military might, the ultimate defeat comes by destroying the organization’s seriousness, attacking its vibe and power until its followers begin to doubt the seriousness of their own mission.

Dictators know that seriousness is essential to power. And tightly controlled propaganda, however funny it is to the outside world, is always a barometer of a leader’s control, especially if the people are forced to swallow it. Dan Wang, the writer and China analyst, recently examined the seriousness of propaganda in his annual letter on China:

When foreign commentators discuss the experience of reading state media, they rarely fail to attach a reference to its “turgid prose.” While some partyspeak is indeed unreadable, I’ve always seen that dismissal as a signal of contempt for the party’s pronouncements, thus deterring people from taking it seriously. But there is reason to treat its content with care. Propaganda might not matter to you, but it matters to the party.

While the outside world often mocks Chinese state propaganda as funny or absurd, the Chinese Communist Party is not ironic. Its seriousness is a proxy for its strength. Indeed, it’s so serious that Winnie the Pooh, the fictional bear that the Internet says bears a passing resemblance to Xi Jinping, has been canceled in the PRC. Why is that? Because seriousness is the maniacal belief in a project greater than oneself. It’s anchored by a type of sacrifice and solemnity that went out of vogue in the United States at the end of the Second World War. If you’re pinpointing a time when America became less serious, it’s around the same time when America began sacrificing communal responsibility in favor of individual pursuits. Though it’s unfair to pin everything on the Boomers, the concept of finding oneself did not exist during the German Blitz. As the sociologist and Freud scholar Philip Rieff wrote in The Triumph of the Therapeutic, “the psychological man” emerged as the dominant moral type in the Western world in late 1960s, replacing tradition and community with the idea of “himself and his own emotions.” Self-actualization through sharing one’s truth is a freshly- baked concept that came out of Esalen and her contemporary communes, seeping into campus and company culture over the last few decades. The movement away from communal mission towards the modern concept of finding oneself left a gaping hole for something to replace the values that once bound us together. As Rieff wrote, “Psychological man may be going nowhere, but he aims to achieve a certain speed and certainty in going.”

It’s no surprise then that in the last few generations, we’ve begun to take the American experiment less seriously. In fact, seriousness is no longer a trait we celebrate in people, replaced by the shield of irony that permeates every conversation, every tweet and so many interactions we have with each other. The ironic voice dominates our online discourse and media culture. Our critics and chroniclers mock the new and the bold and those who are deadly serious about their missions as though they’re relics of a bygone era. “Are you not in on the joke?” We ask. “It’s irony all the way down.”

David Foster Wallace spoke about our descent into irony and characterized its corrosiveness before most of us saw it coming.

Irony and cynicism were just what the U.S. hypocrisy of the fifties and sixties called for. That’s what made the early postmodernists great artists. The great thing about irony is that it splits things apart, gets up above them so we can see the flaws and hypocrisies and duplicates. The virtuous always triumph? Ward Cleaver is the prototypical fifties father? "Sure." Sarcasm, parody, absurdism and irony are great ways to strip off stuff’s mask and show the unpleasant reality behind it. The problem is that once the rules of art are debunked, and once the unpleasant realities the irony diagnoses are revealed and diagnosed, "then" what do we do? Irony’s useful for debunking illusions, but most of the illusion-debunking in the U.S. has now been done and redone. Once everybody knows that equality of opportunity is bunk and Mike Brady’s bunk and Just Say No is bunk, now what do we do? All we seem to want to do is keep ridiculing the stuff. Postmodern irony and cynicism’s become an end in itself, a measure of hip sophistication and literary savvy. Few artists dare to try to talk about ways of working toward redeeming what’s wrong, because they’ll look sentimental and naive to all the weary ironists. Irony’s gone from liberating to enslaving. There’s some great essay somewhere that has a line about irony being the song of the prisoner who’s come to love his cage. -Conversations with David Foster Wallace, Stephen J. Burn

One needs to look no further for evidence of our profound lack of seriousness than the online presence of our government institutions. Take the CIA’s twitter feed, for example. One of the most serious organizations in the world, tasked with the very serious mission of espionage, often tweets as though it’s an Arby’s. Sure, espionage jokes are funny, but do you want the nation’s top spy organization to be telling the joke?

One might ask how comedy interacts with seriousness, as humor is a needed balm for the extreme discourse of our times. But seriousness and comedy are not antithetical. Indeed, when done well, comedy is as serious as any other pursuit. Take South Park, the most ruthless parody show that has managed to survive for 24 years, mocking all that is sacred with lasting effect. How does one reconcile South Park’s brutal comedy with seriousness?

South Park is an emblem of seriousness—so committed to free speech and the ridicule of all things and all peoples that it has never wavered from its mission to excoriate orthodoxy, despite lawsuits and the occasional death threats lobbed at its creators. South Park controversies are so numerous that Wikipedia breaks “South Park Controversies” into its own lengthy page. And that seriousness—that brutal obsession with its mission to lampoon everything —has led to its singular success.

Joe Rogan, who interviews many of the top standup comics working today, has said that there’s never been a better time to do comedy in America because it’s dangerous once again. All things become more serious in times of danger. And in the case of comedy, it forces a comic to be more delicate with a joke, to work harder on delivery and to tiptoe along the lines of what can and can’t be said. The seriousness with which our most dangerous comics operate today does not negate the brilliance or humor of their comedy—they are taking their mission and their jokes seriously. Their audiences laugh louder because of it.

***

When I was in college in the mid 2000s, a professor asked a question during a scholarship interview that still haunts me to this day: are Americans too ironic to make good art? The question took me aback because I was not an artist, but a writer who dreamt of becoming a “cultural critic.” (Talk about a young woman who perhaps took herself too seriously.) My answer to this question was, “Yes, Americans are too ironic to make lasting art. Our art is mostly derivative.” But it was too simple an answer then as it is now. There are small pockets of American seriousness, and they’re the same pockets that are mocked ruthlessly by the New York press and the critics who study American progress through the lens of irony.

The mayor of Miami asking a venture capitalist, “How can I help?” without any irony.

So where are the most serious people in America? What’s amazing is that many are American by choice: just as converts make the best Catholics, so too do immigrants often make the best Americans, taking the experiment more seriously than the cradle to grave kind.

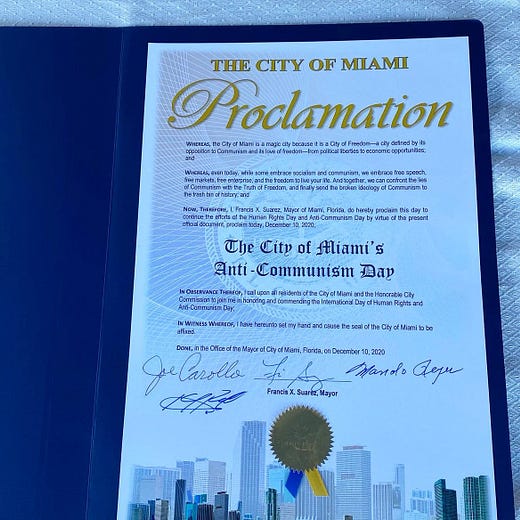

Francis Suarez, the mayor of Miami, recently declared December 10th “Anti-Communism Day” in the City of Miami. For a city built on the backs of those fleeing communism and failed states, the day was a solemn acknowledgment of past suffering. For Americans who don’t have family stuck back in Cuba or those who haven’t experienced the violence and collapse of a place like Venezuela, anti-communism day feels quaint, a relic of a forgotten time.

Silicon Valley—the idea, not the place—attracts some of the most serious people in the world. It is built on the belief that one’s project is greater than one’s history, one’s identity and in some cases, one’s health. It’s why the unending Twitter debate about work-life balance among founders— with some people claiming 80-hour work weeks are normal while others claim they’re abusive— will continue until the end of time. It’s why Elon Musk, both our most humorous and our most serious founder, is tweeting Doge memes all day but is also sleeping in the middle of the factory floor so that everyone in the company can see him splayed out on the concrete. If you truly believe that earth is the single point of failure for humanity, you too would rush to a factory and build reusable rockets to ensure the human experiment exists in perpetuity.

But it’s all so funny, isn’t it? The going to Mars and the space colonization and the free speech obsession and the founders who post massive American flags on their websites to ensure there’s no question about their mission and the future they’re building for. It’s funny when Cubans continue to condemn Castro in the streets and declare Miami a communist-free zone.

It’s all really funny if you’re not serious.

Katherine,

This is a great article.

Lots of directions you could take this.

@Visakanv had a great Twitter thread about what makes America, 'Murica:

https://twitter.com/visakanv/status/1363974562719756288?s=20

"One of these images is a heroic celebration of America

the other is a cringe-inducing, insulting parody of America"

(With a picture of a Bald eagle, fireballs, American flags and monster trucks)

His premise is similar to yours (that Americans don't take themselves seriously, at all) but because America has the most powerful economy, military and media, and because it has a high tolerance for humor and imagination (current environment & pandemic notwithstanding), it is the most entertaining spectacle on the planet. The entry price is learning American culture, which "is like a giant bottom up mythology-meme chaos factory."

Visa goes on:

"I suspect that America's willingness to be cringey-overblown ridiculous in its mythologizing and parodying of itself is a source of it's unfathomable cultural power and influence. it's schoolyard imagination allowed to percolate near-infinitely."

Or as Bruno Maçães put it:

"I increasingly think of China as realityland, America as fantasyland. So the new cold war will be a war between reality and fantasy. A world war in a very literal sense."

https://twitter.com/MacaesBruno/status/1301531491768377346?s=20

I agree with your assessment, overall. I think that this is part of the broader problem of growing up with too much opulence and an ability to be economically fine even if one gets fired for bad behavior. Further, that the internet has provided a mechanism where a person can get positive feeddback from thousands of people with bad taste or a lapse on judgment. The good behavior feedback system is thus degraded, and the longterm consequences are serious but not being addressed. The US was born from an idea of freedom, and it has given rise to a culture of tolerance and acceptance. Unfortunately, that culture has existed now with too much tolerance and acceptance of bad behavior such that the good habits are not sufficiently enforced.